Florida & Parole: Resettlement at Risk

The Refugee Program was designed to address the impermanency of parole. Here's how The GRACE Act could address it today.

History repeats itself.

And it is, now—as humanitarian parole programs once again fail to offer long-term security to those in search of refuge.

Parole, like the Refugee Program, depends on the President. Parolees, unlike refugees, are at risk of having their status revoked, and ultimately, deportation when the Presidency changes hands.

America has been here before. In the 1970s, Congress saw the vulnerabilities that resulted from America’s repeated use of humanitarian parole programs. They saw the costs of parole’s impermanence, its inequity, and its lack of integration services.

That’s why Congress created The Refugee Program. It was designed to remediate the unreliability of parole and offer protections that refugees—and America—could rely on.

That’s why we need The GRACE Act: to fortify the Refugee Program—and offer true, lasting refuge to parolees today.

Humanitarian Parole 101

What is humanitarian parole?

If we want to reform the law, first we need to read it.

Here is the short section of U.S. Code that you need to read to better understand humanitarian parole—8 U.S.C. § 1182(d)(5)(A):

The Secretary of Homeland Security may…in his discretion parole into the United States temporarily under such conditions as he may prescribe only on a case-by-case basis for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit any alien applying for admission to the United States, but such parole of such alien shall not be regarded as an admission of the alien and when the purposes of such parole shall, in the opinion of the Secretary of Homeland Security, have been served the alien shall forthwith return or be returned to the custody from which he was paroled and thereafter his case shall continue to be dealt with in the same manner as that of any other applicant for admission to the United States.

We’ll get to this later—but the very next section prohibits the use of parole for refugees, unless there is a compelling reason to prefer parole to refugee status.

Why? Keep reading to find out.

Humanitarian Parole Today

Biden’s Parole Programs

Responding to the displacement crises in Ukraine, Afghanistan, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Haiti, and Cuba, the Biden Administration welcomed over one million people in search of safety to the U.S. through humanitarian parole.

This pathway was chosen to avoid overwhelming a Refugee Program still recovering from the first Trump Administration and as a work-around for an American asylum system in desperate need of reform.

While the Biden Administration saw humanitarian parole as a tool for politically successful migration management, the Trump Administration sees parole as the opposite.

The political pendulum of parole has swung—from protection to deportation.

Trump’s Response

On day one, the Trump Administration stopped accepting new applicants for all humanitarian parole programs. Last month, the Trump Administration also stopped processing asylum and other immigration claims for parolees from Latin America and Ukraine—stripping parolees of their options to legally remain in the U.S. after their parole expires.

These actions are being challenged in the courts. However, those opposed to parole have had practice litigating these issues, arguing that nationality-based parole programs are “not case-by-case, [are] not for urgent humanitarian reasons, and advance[s] no significant public benefit.” We are likely to see a similar legal battle in the weeks and months to come.

Most recently, President Trump announced that his Administration is considering revoking what little protections parolees have left: terminating their existing parole status, even as the clock runs out.

The Trump Administration, with little oversight, can do just that: even lower-level DHS officials have the authority to terminate parole via mail when, in the opinion of the official, “neither humanitarian reasons nor public benefit warrants the continued presence” of the parolee.

Hundreds of thousands of parolees across the Country—our neighbors, our co-workers, our children’s friends, and our fellow parishioners—are at risk of losing their status and possible deportation.

These communities are now forced to wait and see if President Trump will send them back to a war zone and if the lives they’ve rebuilt in the U.S. will be upended in an instant.

Florida & The History of Humanitarian Parole

The vulnerability of parole is visible, clearly, in Florida—a state whose history is braided with parole.

Cuban Refugee Crisis of 1959

In 1959, following the Cuban Revolution, humanitarian parole enabled Florida to become a welcoming gateway for Cubans escaping the Castro regime. However, parole only offered these refugees temporary protection—much like parole programs offer refugees today.

In 1966, recognizing the necessity to provide these communities with permanent status, Congress passed the Cuban Adjustment Act. Because Congress created a pathway for these parolees—essentially amending the parole statute for the Cuban population—to obtain lawful permanent residency, they were able to find long-term safety in Florida and rebuild their lives.

Florida has benefited immensely from this policy (despite changes across Administrations), with Cuban Americans becoming core economic, political, and cultural contributors to the Sunshine State.

Refugee Crises in Florida Today

Unlike 1966, no adjustment acts—for paroled Afghans, Ukrainians, Haitians, Nicaraguans, or Venezuelans—have been passed by Congress.

Humanitarian parolees across Florida—and the U.S.—remain at risk.

Manuel Castaño, a 39-year-old human rights activist from Nicaragua, received parole in March 2023 after being sponsored by his uncle. Now working in building maintenance in South Florida with his wife and 13-year-old daughter, he faces an uncertain future when his parole expires in March 2025. "Going back to Nicaragua is not an option," he says, noting the political persecution he would face after speaking out against the Ortega regime.

The Castaño family is one of thousands trapped in limbo. Because parole is vulnerable, communities are vulnerable.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

From Ad Hoc Solutions to Structured Programs

The Refugee Act

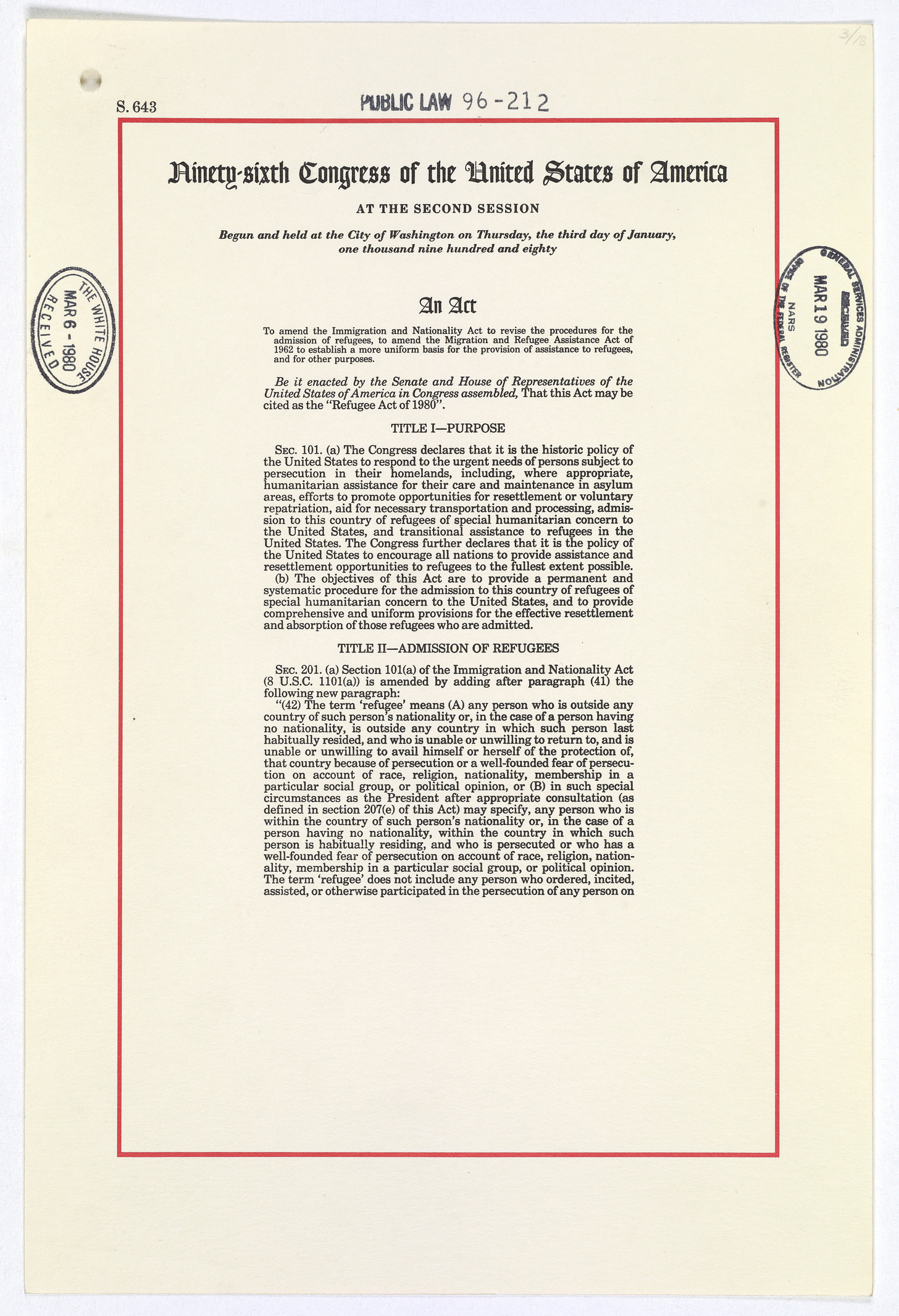

America has addressed the vulnerabilities of parole before: by passing The Refugee Act of 1980 and creating the Refuge Program.

Remember how the statute that governs parole prohibits its use for refugees, unless parole is preferential to refuge status? Yup, you guessed it—that clause was added by The Refugee Act.

For seven decades, humanitarian parole has been a critical tool in U.S. immigration policy. Established during the Truman Administration through the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, parole gave the executive branch flexibility to address humanitarian crises without requiring congressional action.

However, this flexibility came with costs. By the late 1970s, the repeated use of parole to address humanitarian emergencies had become chaotic for parolees, for services providers, the United States, and our allies.

To address these concerns, Congress passed The Refugee Act of 1980, creating the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP). Congress explicitly designed The Refugee Program to address the problems of parole; The Refugee Act’s two primary objectives for the Refugee Program are to "provide a permanent and systematic procedure" for refugee admissions and "comprehensive and uniform provisions" for resettlement services.

Sidebar: We’ve written about the history of the Refugee Act before.

Parole is neither permanent nor systematic, comprehensive nor uniform.

The Refugee Program is.

For much of its history, the Refugee Program functioned as intended. The U.S. resettled an average of over 95,000 refugees annually, Presidents from both parties welcomed refugees to the U.S., and more than 3 million people rebuilt their lives in America.

But when the executive branch fails to adequately equip the Refugee Program to manage emergent displacement crises, parole resurges as the humanitarian pathways of choice—and the chaos of its vulnerabilities returns in full force.

Cuban Refugee Crisis of 1980

The first test of the Refugee Program—the Cuban Refugee Crisis of 1980—warned us about what would become of our humanitarian immigration systems if we failed to adequately equip the Refugee Program.

After Castro opened the port of Mariel in 1980, President Carter issued an emergency presidential determination to admit those fleeing 1980s Cuba to the U.S. as refugees.

However, with the ink hardly dry on the Refugee Act, the fledgling Refugee Program was unprepared to successfully process a rising number of Cuban arrivals. President Carter returned to the use of parole to offer Cubans safe haven.

Ted Kennedy, the primary sponsor of the Refugee Act, gave a prescient warning for our times:

“[T]he Administration abandoned use of the [Refugee] Act in favor of an ad-hoc, short-term solution: temporary use of the so-called ‘parole authority...

The decision to ignore the new law poses some troubling questions about the future of the Act.”

These same words could be said today.

The first parole program created by the Biden Administration was designed to offer welcome to Afghans without overwhelming a Refugee Program still recovering from the first Trump Administration, much like parole was used in lieu of a barely-formed, under-equipped Refugee Program in the 1980s.

Emergency Response

While humanitarian parole plays a critical role in providing humanitarian protection, Congress created the Refugee Program to ensure that those welcomed to the U.S.—even during emergencies—could remain in the U.S. permanently.

For example, in 1999, the U.S. processed Kosovar evacuees as refugees—an alternate model to today’s parole programs.

Much like participant’s in today’s Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan, and Venezuelan or Uniting for Ukraine parole programs, some refugee processing happened remotely—namely, approval of their “Registration for Classification as a Refugee” form and group designations.

Much like Afghans were processed as parolees at safe havens across the United States, Kosovars were processed at Fort Dix—but with the full and permanent protections of refugee status.

While not all parolees would meet the requirements necessary to become refugees, we have made exceptions before (see NSDD-93 and the Lautenberg Amendment) —and could again (see David Martin’s proposals for legislative reform).

The Refugee Program was designed to be the primary pathway for humanitarian admissions, preferential to parole—even in emergencies. While parole does not offer refugees a pathway to permanency, the Refugee Program was designed—and has—done just that.

It just has to be equipped to do so, in perpetuity—and that’s where The GRACE Act comes in.

The GRACE Act

With a bolstered Refugee Program as envisioned in the GRACE Act (read more about the GRACE Act here), parolees would no longer wake each morning wondering if today is the day that they'll be forced to return to danger.

Congress can provide the continuity and certainty necessary for a functional and orderly Refugee Program, equipped to respond to crisis, by codifying a statutory floor for refugee admissions.

The stories unfolding across Florida today—of lives rebuilt only to hang by the gossamer thread of executive discretion—highlight the human cost of our repeated reliance on parole programs.

When people fleeing persecution can arrive as refugees rather than parolees, they gain not just legal protection—but the psychological security to truly heal and rebuild their lives. Temporary refuge is not really refuge at all.

The GRACE Act offers what parole never can: the promise that America's welcome is neither temporary nor contingent on who sits behind the Resolute Desk.

Parolees deserve a Refugee Program they can rely on. America does too.

Click here to contact your members of Congress about The GRACE Act.

Thanks for reading Save Resettlement.

Next week, Georgia & The Next Ten Years.

Until then, we recommend listening to This American Life and attempting to identify a new bird in your neighborhood. Hope, in any form, is sustaining.